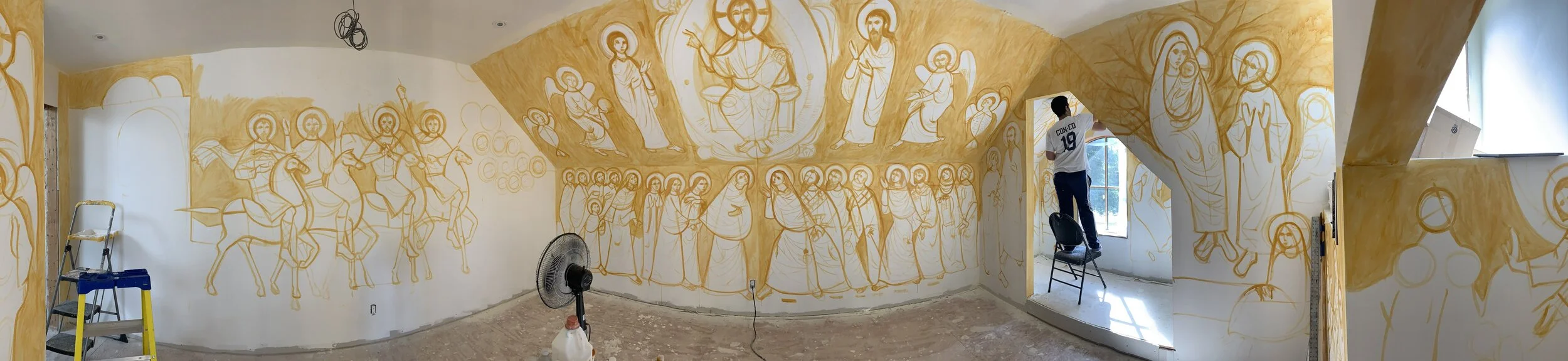

THE CHAPEL OF INTERCESSION

deriving its name from the greek word deisis, (δέησις, "prayer" or "supplication") this chapel presents a program of wall paintings that focuses on the biblical and hagiographical role of the family in the understanding of the church. there is an emphasis on the role of intercession within the family both in the universal church, and in the family, the microcosmic church.

INTRODUCTION

The colour scheme aims to reflect the warmth of the resurrection and new life. In Ancient Egypt, the colour orange was associated with the sunrise, or Kheper, roughly translated as “to come into existence” or “to become.” Dawn simultaneously represented incarnation and resurrection, particularly in the context of the role of the sun-god Ra. Thus a subtle orange reflection graces all the faces in the room, as the figures beam with the glorious reflection induced by the incarnation and resurrection of the Son which they pursue and are illuminated by. The notion of Desher described the desert and its various associations to the time of day through the colour of sand, with bright pink representing dawn, yellow depicting midday, and red depicting dusk. The entire landscape in the chapel thus rests on the light pink hue of Desher, and creation responds to and participates with the figures that surround it. The singular landscape, and at most times, singular plane, suggests a transcendence of time and space across the various scenes and figures that all adhere to the same universal theme. The passage from death to life in the resurrection implied by the colour thus associates the landscape to Paradise itself, and the participants in the procession of the Church, barefooted and unbound to the world, guide the supplicant to join in the atmosphere of paradise. If the family is a nucleus of the spiritual existence of an individual, propelled by the work of intercession, from it also must emerge the rebirth, or resurrection of the individual in the spiritual dynamic of the family and the Church. The emptying of the self in interceding or pleading marks a kenotic behaviour that, if interpreted as the death of the self, is fulfilled by the new life that the intercession strives towards achieving. The majority of the figures are also dressed in white, called to participate in the joy of the resurrection and united visually to reinforce the overall concept of unity. Technically speaking the unison in neutrality of colour also maintains the quietness of the room despite its figurative density. The heightened usage of creams, whites and light colours also aims to push forth the concept of light, as a revelation to intercession, a response to supplication, and a binding force into the beauty of God- the glorious beauty willed and intended for man.

THE EASTERN WALL

The “Eastern” or focal wall depicts the Deisis, with the bottom register depicting five women from the Coptic Synaxarium who brought their families to Christ. It is a continuation of the procession that begins on the north wall, serving as a direct trajectory from the doorway to the throne of Christ. The movement of the wall is designed to follow that of the Book of the Dead, in which the deities and sometimes family members lead the worshippers by the hand into paradise, as is being presented on this wall. The top register depicts a typical deisis scene, (found in the monasteries of St Macarius and the monastery of St Antony in the Coptic tradition). Sophronius of Jerusalem (560-638) cites the existence of this composition as early as the sixth century, stating “We saw a very grand and wondrous image, representing in the middle a certain picture of our Lord Jesus Christ and on the left the Mother of Christ, Our Lady the ever-virgin God-bearer Mary, and on the right the Forerunner, Baptizer of our Savior. Further, a choir of prophets and apostles and a group of martyrs gathered before the image, and with knees bent and heads bowed, they fell down before the one God.”

Christ as Pantocrator is the climax of the room’s program, surrounded by the four incorporeal creatures (as all creation worships Him), with each of the four creatures associated with the four evangelists, as first interpreted by Iraneaus (Matthew as man, Mark as lion, Luke as calf, and John as eagle). The interceding Virgin and John the Baptist, His family, stand as the primary intercessors and the earliest witnesses to His divinity. They are dressed in outer brown cloaks and inner red tunics, representations of humility (associated with dirt and flesh) and martyrdom (martyr translates directly as “witness” in Greek). The placement of Christ and His family as the centre of attention in the room evokes the worshippers to invite Christ into their own families and to model theirs after His. Surrounding these three are archangels Michael and Gabriel and the Cherubim and Seraphim who compose the heavenly synaxis, forming the mystical body of the Church.

theodota and her five sons

22ND OF HATUR

On the lower register (beginning from the far left), Theodota- with her five sons, Cosmas, Damian, Anthimus, Leontius, and Eupreprius (the child)- approaches the throne of Christ. Theodota is understood to have witnessed the torutre of her five sons, and upon comforting them and firmly reminding them that death supersedes the denial of Christ, she was murdered in front of her five children, compelling them to follow suit. Thus, Theodota holds on her forearm a scroll inscribed with her intercession, “It is better for you to die than to deny Christ.” Cosmas and Damian, the twins in the back, hold their medicinal instruments and containers, as they were renowned physicians in their time, famed for being unmercenaries (tending to the sick without charge). Eupreprius holds in his hand an ankh, the ancient Egyptian symbol of life which, in this context, is associated with the life found in martyrdom and sacrificial love. The family is mentioned in the commemoration of the saints of the midnight psalmody.

Sophia and Her Three Daughters

30TH OF TUBAH

Preceding Theodota is Sophia (Gk. Wisdom) with her three daughters Pistees (Faith), Helpis (Hope) and Aghapi (Love). They were twelve, ten, and nine, respectively. They were pushed to worship the hunter goddess Artemis, an intercessor during war, but the three sisters brought to emperor Hadrian their peace and composure as their bow and arrow. Much like with Theodota and her sons, these three sisters were brutally tortured before their mother, and they refused to forsake Christ, finding encouragement in the power of their mother’s prayers that cooled the fire of their furnaces and broke the devices of their torture. Wisdom takes Love by the hand, and in turn Love looks intimately to the viewer in an invitation to join her in participating intimately with Love and Wisdom Himself.

macrina and her three brothers

ST BASIL THE GREAT- 6TH OF TUBAH | ST GREGORY OF NYSSA- 21ST OF TUBAH

On the opposing side is Macrina the younger with three of her brothers, Basil the Great, Peter of Sebaste, and Gregory of Nyssa, all dressed in accordance to their clerical ranks. Macrina is credited with educating these three brothers, raising two of the greatest theologians in Orthodox Christianity. Gregory wrote her biography of asceticism and holiness in a work titled the Life of Macrina. Gregory describes the life of his mother and sister as,

“...estranged from every worldly vanity, thus emulating the life of the angels... For them, continence was a sumptuous fare; obscurity was glory; poverty and the saking off of every material object, like some particle of dust, was wealth.”

monica, augustine, demiana, and mark

STS MONICA AND AUGUSTINE- 22ND OF MESORE | ST DEMIANA- 13TH OF TUBAH | ST MARK- 5TH OF APIP

Behind these four are Monica and her son Augustine, two monumentally influential figures in early Christianity. Born in what is now modern day Algeria, these two saints had a complex relationship. Driven by his love for sensuality and pleasure, Augustine began to pursue a life of carnal intention in Carthage. He also delved into Manichaeism, straying from the bids of his mother. For nine years he taught as an academic in Thagaste and Carthage, and it is during these years that his mother was famously comforted by a bishop that “the son of many tears will not perish.” Augustine is considered the first writer in history to produce an autobiography, Confessions, in which he details the intricacies of his conversion. His famous quote appears on a scroll in his hand, “our hearts are restless until they find rest in You.”

Following Monica and Augustine are the prominent St Demiana and her father Mark (Markos). Mark is portrayed in an attire characteristic of a third century Egyptian governor. The wreath of his head is reminiscent of those worn by the figures in the famous Fayum mummy portraits. There are 3 existing manuscripts written between 1732 and 1831 C.E. which were transcribed from a sixth century manuscript penned by Bishop John of Burullus during the papacy of Pope Damian, the 35th patriarch of Alexandria (563-598 C.E). These recently translated accounts contain a highly detailed account of the life of St Demiana, including her relationship with her father. Reproduced below is the account of her dealings with him:

“Mark the governor was deceived; he immediately offered incense to the idols, bowed down before them, and thus renounced the God of heaven… the news reached his daughter, the Lady Demiana, and she hastily arose, left her palace, and went to meet with her father. When she entered in his presence, she did not greet him. She said to him, “What is this sorrowful news which I have heard, that you have forsaken the religion of Christ our God, obeyed the Emperor, and worshiped the idols?! “I would have rather heard the news of your death as a Christian, living with Christ eternally, than your life as an idolator, dead in Hades… father, Return to God.” When Saint Demiana’s father heard these words from her, he immediately came back to himself, just as one drunken awakes from wine. At once, he cried loudly in weeping and lamentations… then speedily arose and journeyed towards the city of Antioch… He proclaimed to the emperor, “I believe in the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, the One God, Amen!”... They escorted him to the place of beheading in the city of Antioch… an evil and wicked soldier cut off his head with the edge of the sword and cast it away. Hence, his pure spirit ascended to Paradise by the hand of the Eternal Creator, whom he loved.”

the western wall

The “Western” wall depicts scenes from the Old Testament regarding the family- the back and largest wall depicts the hospitality of Abraham; the three triangular vaults depict Noah’s sacrifice, Jacob’s dream, and Moses receiving the law, respectively; and the accompanying walls depict Ruth, Boaz and Naomi, Daniel, David, Tobias and Archangel Raphael, and Joshua the prophet. While the majority of the wall consists of figures that participate in the genealogy of Christ (Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Judah, Boaz, and David), the figures also identify themes of intercession and family within Old Testament narratives. The portrayal of Old Testament narratives with those of the New Testament and the Church supports the holistic and cohesive image of the presence of God in all epochs of the narrative of salvation, and the unifying presence of common salvific themes throughout the ages.

joshua, daniel, raphael and tobit

JOSHUA 24 | DANIEL 2:44 | TOBIT 3:17-9:6

Above the door is Joshua the prophet, dressed in military attire, holding a scroll that proclaims, “as for me and my house, we will serve the Lord.”- a phrase exclaimed in fidelity of worship to God. Next to him is Daniel, also loyal to worshipping the true God, and on his scroll he declares, “The God of Heaven will set up a kingdom which will not be destroyed.” This alludes to the Church which Daniel faces and, in his context, the role of the people of God in acting as a family in times of alienation, estrangement, captivity, always remaining faithful to Jerusalem, the city of God, “the dwelling of the righteous,” the abode of the family. A Tefillin is bound to his head in accordance to Jewish custom.

Beneath Daniel the prophet is Tobias with Archangel Raphael. The composition was painted to mirror the wall paintings of Faras, in which larger, overshadowing figures would stand over as intercessory saints or angels for emperors, clergy, patrons, or supplicants. Tobias, the son of Tobit, went out with Archangel Raphael on a journey to find money to cure his father’s blindness. The role of Archangel Raphael as intercessor brings to fruition Tobias’ journey, who catches a fish and uses the heart, liver and gall as both spiritual and medicinal objects of healing.

noah

GENESIS 6-9

The innermost triangular truss presents Noah offering a sacrifice from outside the ark. The ark carries parallels to the Church, and thus the family of Noah becomes the idealistic family that acts as the microcosm of the heavenly realm in the earthly flood of distractions and distance from God. Noah is depicted accompanied by his wife, his three sons, and their wives, kneeling in prayer, while Noah supplicates to God and offers a burnt sacrifice at the altar he has built (as the Eucharist is the uniting point between man and God). Noah, as “head of the Church”, intercedes for humanity with God, and at his knees rests an olive branch. The olive branch at his knees is the same one in the hands of archangel Gabriel, and it symbolizes the covenant of amity and peace between God and man- in the hands of archangel Gabriel it bears the connotation of the reconciliation with man brought about by the incarnation, and at the knees of Noah the reconciliation with man brought about by the new and renewed creation, the earth in its resurrection and new life after death.

the hospitality of Abraham

GENESIS 18

Below Noah is the hospitality of Abraham. The climax of the western wall depicts the events entailed in Genesis 18. Abraham is shown with his offerings of hospitality (the bowl, pitcher, bread, and the slaughtered calf) while the three visitors rest under the oak of Mamre. Three visual references to the Eucharist are made in this icon -the first being Abraham approaching God with a cloth between his hands, the second being the bread and wine on the table before Christ, and the third being the oak of Mamre itself, as a type of the cross. Sarah stands at the entrance of the tent and laughs in response to the prophecy of the birth of Isaac. In a maneuver of visualizing dramatic irony (as “mamre” itself translates into “insight”), Isaac stands to the side of the scene and presents to us the discussion within which his birth was pronounced. Isaac’s name translates directly into “the one who laughs” and, as Sarah describes, was bestowed on him since, “God has brought [her] laughter, and everyone who hears about this will laugh with [her].” (Genesis 21:6). Isaac is dressed in white and red to parallel Christ. The firewood in his arms resembles the cross, and so Isaac stands not only as a fulfillment of the prophecy painted in the scene, but as a prophecy in and of himself of the sacrifice of Christ. At the end of the narrative of the hospitality of Abraham, Abraham intercedes for Sodom, and has a lengthy discussion pleading for the salvation of those residing there.

The united and harmonious manifestation of three angels, accompanied by Abraham’s “singular speech” accommodated some to associate the three visitors with the Trinity. This has led to a myriad of complexities in theological interpretation, and, as a result, the visual and iconographic interpretation as well. Throughout the history of the iconography of the Hospitality of Abraham, various approaches indicate a central or pronounced figure as Christ- a cross in the halo, a distinct halo colour, distinctive clothing, a blessing hand, and in some rare occasions, a vesica. These visual implications correspond to the interpretation that the three angels consisted of God accompanied by two angels. In the painting, a subtle cross supports this notion, particularly since the painting focuses on the narrative as a whole as opposed to simply the mysticism of the three visitors. Andrei Rublev’s approach to his icon of the Trinity calls for the viewer to participate with the angels in communion with them, ergo the inclusion of the eucharistic elements that were previously mentioned. The elements can be applied to either visual interpretation but are highly emphasized in Rublev’s.

jacob and moses

GENESIS 28:10-22 | EXODUS 24:12-18

Opposite the sacrifice of Noah is Jacob’s ladder. Jacob is reclined and, in his sleep, sees angels ascending and descending a ladder that leads into heaven. Jacob’s dream occurs at a point of tension in which his relationship with his family is strained and, as outlined in the dream, God proclaims that “...in [him] and in [his] seed shall all the families of the earth be blessed.” Irenaeus in the second century describes the Christian Church as the "ladder of ascent to God." The ladder also alludes to the Virgin, described as the “uniting place” of heaven and earth. The eighth part of the Saturday theotokia and the second part of the Tuesday theotokia both allude to the Virgin as the ladder which Jacob saw. Her role as intercessor corresponds fluently to her role as a personification of the ladder itself.

St Gregory of Nyssa describes Moses as having climbed the ladder of Jacob in his mystical ascent upwards, which leads the viewer to the opposite side of the same triangular truss- Moses receiving the law. Moses is depicted ascending the mountain to receive the two tablets of the law. At the foot of the mountain are his siblings, Aaron and Miriam, who holds a timbrel in her hand. Moses takes off his sandals and climbs upwards, interceding for the people of Israel. On the tablets are the numbers 1 to 10 written in Coptic. In Coptic the numeral for 10 is ⲓ︦, which is comprised of the letter iota. This is referenced in the first part of the Sunday theotokia, “the tablets of the covenant whereupon are the ten commandments which are written by the finger of God- they have directed us, to the Iota, the name of salvation, of Jesus Christ.” The Coptic spelling for the name Jesus is ⲓⲏⲥⲟⲩⲥ, so the play on words describe Christ, the Word of God, the Logos, as the fulfillment of the law which Moses received. This is paralleled by the gospel book in the hands of Christ as Pantocrator on the opposing wall, the name of Christ, or the name of salvation, is inscribed on the cover of the gospel book, which in and of itself is an icon of Christ who is the word (the central cross is Christ surrounded by four smaller crosses symbolizing the evangelists), and the Word of God is fulfilled in Christ.

joseph

GENESIS 44-45

At the bottom apex of the two trusses is an image of the mercy of Joseph towards Benjamin and Judah, with Judah interceding for Benjamin. Joseph is dressed as a vizier, clothed in white pleated linen (a symbol in ancient Egypt that denoted impartiality), and wearing a wig, false beard, and a golden necklace, standing in his palace. The curtain behind him contains eleven stars and the sun and moon bowing towards him, in reference to his dream in Genesis 37:9. In contemporary Coptic art curtains drawn to the side often represent revelation, and thus the curtain is used to depict the revelation of the truth, both regarding Benjamin and the identity of Joseph himself as a member of the family that supplicates before him. Benjamin is dressed in pure white to reflect his innocence, and before him is the silver cup from which the accusation against him arose. The shape of both the cup and the column behind Judah are references to the lotus flower, which, in ancient Egypt, was a hugely popular symbol of rebirth and salvation from death through resurrection, which was fitting in the case of Benjamin.

ruth, boaz, naomi, and david

RUTH 1-4 | 1 SAMUEL 17:12-36, PSALM 151

Next to Salome in the lower left corner of the western wall lie Ruth, Boaz and Naomi in recline in a wheat field conversing. Ruth and Naomi intercede for each other at varying points of the narrative, with Ruth displaying remarkable loyalty to Naomi. The wheat sheaves in Egyptian painting were associated with the Field of Reeds (A’aru) which, mythologically, was the physical manifestation of paradise itself. With the formation of their “Church”, Ruth, Boaz, and Naomi cultivate a harvest of love and invite the viewer to join with them.

Above the wall with Ruth, Boaz and Naomi is their descendant David, seated and playing a harp with ten strings. This particular image depicts psalm 151. Surrounding him are his seven brothers, and David is painted the largest of them as the intercessor for the Israelite nation before Goliath (using Pharaonic hierarchical scale as a visual device). David plays a largely significant role in the liturgical and hymnological facets of the Church- both through the psalms and lyrical references. The ten strings reference the hymn ⲁⲧⲁⲓ ⲡⲁⲣⲑⲉⲛⲟⲥ (which venerates the Virgin through the ten strings of David’s harp resting on his knee). The hymn ⲁⲛⲟⲕ ⲡⲉ ⲡⲓⲕⲟⲩϫⲓ is derived directly from psalm 151 and describes the role of David among his brothers, both as an element of his family and an intercessor against the “disgrace” of Israel:

“I was small among my brothers, and the youngest of my father’s sons. I was shepherd of my father’s sheep. My hands made a musical instrument; my fingers strung a lap harp. Who will tell my Lord? The Lord himself, the Lord hears me. The Lord himself sent his messenger, and took me away from my father’s sheep. He put special oil on my forehead to anoint me. My brothers were handsome and tall, but the Lord did not take pleasure in them. I went out to meet the Philistine, who cursed me by his idols. But I took his own sword out of its sheath and cut off his head. So I removed the shame from the Israelites.”

the northern wall

The “Northern” wall portrays the Church as a procession of a synaxis of saints that build a trajectory from the doorway and continues onto the eastern wall, and ends with the wall with Paul and Phoebe the deaconess. This procession is loosely defined as an exploration of the Church as a holistic type of family. The contemporary church looks out to the martyrs and ascetics to guide the way to the ultimate focal point on the eastern wall. The combination of saints was largely informed by the patron saints of the user, and an effort was made for them to be organized, arranged and presented in a cohesive and categorical manner.

four clerical orders

ST HABIB GIRGIS- 21ST OF AUGUST | ST PISHOY KAMEL- 21ST OF MARCH | ST ABRAAM THE BISHOP OF FAYUM- 3RD OF PAOUNA | ST POPE KYRILLOS THE SIXTH- 30TH OF AMSHIR

Nearest to the door are four contemporary and recently canonized saints who represent the four orders of the clergy: the Patriarchs (Pope Kyrillos the sixth), the Episcopate (St Abraam the bishop of Fayum and Giza), the Priesthood (Fr Pishoy Kamel), and the Diaconate (St Habib Girgis). All four saints pushed massive spiritual, hegemonic and academic revivals within the Coptic Church, leading a “procession” of renewed love for Christ and leadership of his flock in the steps of the early Church, as represented here. The censer in Pope Kyrillos’ hand serves as a suggestion of the heavy implications of liturgy in their everyday conduct and behaviour, most fittingly placed in the hands of Pope Kyrillos. St Abraam carries a money bag to represent his charity, while Habib Girgis holds a scroll that reads, “It is beneficial to gaze unto the conduct of the saints, and, through grace, to progress to perfection as they lead in the procession of virtue.” This quote is the first item that the worshipper is confronted with upon entering the room- and it serves as a set of instructions in a call to join the procession that is unfolding. The contemporary Church, by nature of being contemporary, serves as the starting point nearest to reality from the door, as the room delves deeper into the otherworldliness of the heavenly family.

the equestrians

ST ESKHIRON- 7TH OF PAOUNA | ST MINA- 15TH OF HATUR | ST MERCURIUS- 25TH OF HATUR | ST GEORGE- 23RD OF PARAMOUDA

Following the four contemporary saints are four great equestrian saints of the Coptic Church- St Eskhiron, St Mina, St Mercurius, and St George. These four ride triumphantly as victors of war in the procession of victory, and, together with the ascetics that stride before them, visualize the verse from the conclusion of the Watos Theotokias ``all the martyrs shall come bearing their afflictions, and the righteous shall come bearing their virtues.” A parallel is built between the martyrs and ascetics as “struggle-bearers'' calling the Church to follow in their direction. The contemporary Church looks to them for intercession and they, in turn, lead them to the throne of Christ, just as the five women do with their families on the eastern wall. All four horsemen restrain their horses into their peaceful strides, for these four have restrained their passions- having been taunted with women and wages- to pursue the heavenly stride to the Kingdom of Heaven (Mt 11:12).

The first of the equestrian saints is St Eskhiron (commonly known as Abaskhiron). His name translates into “mighty” which is the same adjective (Ⲓⲥⲭⲩⲣⲟⲥ) used in the Trisagion. St Eskhiron is attributed with having moved and saved a church named after him from Qellin to el-Beho, in an incident where a mass wedding was disturbed by a violent mob. St Eskhiron, therefore, bears in his arms the church he moved, which parallels the contemporary Church. His role as intercessor extends beyond the miracle attributed to him and into the lives of those who stand before him. On his saddle are the words (in Coptic), “He refused the earthly, sought after the heavenly, and fought in the stadium of martyrdom.” Riding before St Eskhiron is St Mina, with his arms outstretched in prayer as is customary for his depiction. Before St Mina is St Mercurius bearing two swords. Michael descends to St Mercurius and grants him a golden sword with one hand, while the other crowns the martyrs with a golden wreath . This golden wreath would have been the customary headwear for the very emperors under whom these equestrians were martyred. As for the second sword, tradition holds that in a military campaign against the Berbers, Mercurius was granted a second sword with which he victoriously defeated his enemies, bringing him into the graces of Emperor Decius. The Coptic text on the saddle underneath him reads, “He ascended into war with the power of Christ'' (excerpted from his doxology).

The small battalion is led by St George, the “prince of the martyrs.” St George triumphantly spears a small serpent with a cross, building a direct visual parallel with images of the slaying of Apophis from Ancient Egypt. This serpent was associated with chaos and, the antithesis of order, resembled all evil and disorder in the universe. St George brings order to the Church with the expulsion of not only chaos, but Paganism itself, not only in the literal sense but, in the context of these four martyrs, the paganism of worshipping earthly, military, economic, or governmental power, all of which were austerely refused by the horsemen. The serpent is also mirrored with that in the garden of Eden, and thus the source of enmity between God and man is renounced in the procession towards His kingdom. The cross at the head of St George’s spear emphasizes this. The small and insignificant size of the serpent reminds the viewer of the grace of Christ in conquering Satan and the passions in the pursuit of the heavenly. The Coptic text on the saddle underneath St George reads, “Hail to the morning star” as he is described in the Morning doxology. The morning star (Venus) often appears in the east before the sun does, prior to sunrise, and for that reason St John is referred to as the morning star in the Eastern Orthodox Church -the star that is the proclaimer of the Rising Son. In this case, St George proclaims the victory of the rising Son in his victorious battle.

the ascetics

ST ONUPHRIUS- 16TH OF PAONA | ST CYRUS- 8TH OF APIP | ST MOSES THE STRONG- 24TH OF PAONA | ST PAUL- 2ND OF MESHIR | ST ANTONY- 22ND OF TUBAH | ST ATHANASIUS- 7TH OF PASHANS

Continuing the procession are six ascetics and St Athanasius, the twentieth patriarch of Alexandria. The etymology of the word “asceticism” (Gk. ἄσκησις) relates to the training undergone by athletes in their exercise. The ascetics thus complement the equestrians in their synonymous enactment of Matthew 11:12. The first two saints are hermits, Sts Onuphrius (Nopher) and Cyrus (Karas). Their biographies entail that they lived in uttermost seclusion, and yet participated as proponents of the body of Christ.

Following these two are St Moses the Strong and his teacher St Isidore. St Moses is the only one dressed in red to characterize him for his martyrdom. He is led by the hand of St Isidore in a continuation of the “Book of the Dead” composition on the eastern wall. The facet of discipleship furthers the thematic exploration of familial intercession. St Moses also carries with him a bag with a slit draining sand, in reference to the famous narrative in which, (with some variations regarding the object he carried) upon being called to a meeting for the reprimand of one of the monks, St Moses tears a slit in a bag full of sand and walks with it to the meeting. In response to the curiosity and confusion of the monks he announces, “My sins run out behind me and I do not see them, but today I am coming to judge the errors of another."

The bottom row consists of St Paul the hermit, St Antony the great, and St Athanasius the Apostolic. The three carry the cloak of St Athanasius. Jerome recorded that St Antony buried St Paul in the cloak of St Athanasius, and that St Paul’s cloak was given to St Athanasius by St Antony and was worn by him during liturgical services three times annually. This exchange of garments among the three saints reflects an attitude of brotherhood which parallels the attitude of fatherhood and sonship above them. The saints of the procession on the north wall thus reinforce the concept of intercession holistically, however the relationships between various saints on this wall also drive forward the familial understanding that exists within the Church as a single body.

the southern wall

The “Southern” wall consists of a large wall fixed to a small side room, both of which carry the theme of familial intercession within the New Testament. The Southern wall thus runs in continuity with the Western wall, while the Northern with the Eastern one. The southern space is dominated by the Holy Family in Matareya, across from Paul and Phoebe the deaconess. Within the side room is the vision of Cornelius underneath the scene of the baptism of his household, the raising of the daughter of Jairus, Christ as the Good Samaritan, and Christ in Bethany. Sts Mark the Apostle and Marina the martyr also appear in this space.

the holy family in matareya

MATTHEW 2:13-23

The flight to Egypt is the most characteristically Coptic and Egyptian iconographic composition in contemporary Coptic art. It contains many references to Egyptian mythology and, by using such, reflects that fulfillment that Christ brought into the land of Egypt. The particular image used in this chapel was that of the family in Matareya, when they rested under the shade of a large sycamore tree. The tradition holds that during the flight to Egypt, the Virgin Mary, Joseph, Salome and Christ all sought the shade of a large sycamore tree in Matareya. This image depicts the Virgin reclined, dressed in a dark brown and red, holding- and presenting- to us the Christ child who is presented as the Eucharist. She carries in her left hand a thin cloth in between her fingers, a simplified recalling of the handkerchief used by the faithful in receiving communion and the maniple used by the clergy for enshrouding the Eucharist. Christ is depicted swaddled in mummy wrappings, alluding to His salvific death and burial.

In Ancient Egypt, the goddess Isis (Ⲏⲥⲉ) was among the major deities of the ancient faith, up until late Antiquity. She was primarily venerated as a “Divine Mother”, and was a prototype for the Pharaoh’s mother. As mother to both Pharaoh and the god Horus, she also played an intercessory role among Egyptian laypeople to the gods. Often depicted anthropomorphically, she bore either the Sun as a disc or the Egyptian hieroglyph for “throne” on her head. The goddess Isis was also alternatively depicted as a sycamore tree that suckled Pharaoh. The Virgin Mary, described liturgically as “Wider than the Heavens”, usurped the role of Isis as the bearer of the sun on her head. The Virgin now bore the Sun in her womb, and the goddess that once bore and protected the throne of Osiris and Pharaoh became the throne of God Himself, the dwelling place of the Incarnate Logos. Thus, the sycamore tree behind the Virgin that represents her is a symbol of Paradise, the dwelling place of Christ. The bird on her left carries a double meaning - it alludes to the god Horus (who overshadowed the throne of Pharaoh and Pharaoh himself- now the Virgin and Christ) as well as to the pure turtledove that the Virgin is described to be and is more frequently recognized as. This same dove appears in the scene of Noah, and these analogous images appear in the matins doxology to the Virgin,

The pure turtle-dove that declared in our land and brought unto us the Fruit of the Spirit- the Spirit of comfort that came upon your Son in the waters of the Jordan (as in the type of Noah)- for that dove has declared unto us the peace of God toward mankind. Likewise you O our hope, the rational turtle-dove, have brought mercy unto us and carried Him in your womb.

As for the bird on the opposing side, next to Joseph (who has his hands raised in obedience and submission to the will of God), is a nilotic ibis which, once again, in Egyptian mythology was associated with the god Thoth, the ancient god of wisdom. Thoth encounters Wisdom Himself, and the wisdom of antiquity is superimposed by the Logos, the rational God who brings fulfillment and order to all things. The carpet that the Virgin sits on is inscribed with the Coptic text of Isaiah’s prophecy of the entry of Christ into Egypt, “Behold, the Lord rides on a swift cloud, and will come into Egypt” (Isaiah 19:1). At the feet of the Virgin and Joseph rests Salome on the riverbank of the Nile. She invites the viewer to drink from it and collects water from the riverbank to bathe Christ and wash His clothing (as was the role she was described to have had in Coptic tradition). The Nile represents the fountain of Life, Christ-the Eucharist- as well as the Virgin, the life-giving spring. Sitting at their feet, Salome sits to entertain this analogy with the viewer.

Mark the apostle is painted in a small triangular space adjacent to the scene of the Holy Family, as he returned to the same land after their departure to establish the Church which Christ had “established an altar” in. His placement contextualizes his importance to the Egyptian Church, their intercessor at times, and he extends his hand with a feather between his fingers in anticipation for the gospel he will write and disseminate, in parallel with what is occurring in the scene to his left- the dispatching of Phoebe the deaconess by Paul the Apostle.

paul and phoebe

ROMANS 16:1-2

Paul describes that he dispatched Phoebe in the book of Romans, commending her, describing her as a deaconess and as an “advocate” or intercessor, προστάτις in Greek. He encourages the Romans to welcome her into their community as one would with the saints. Here too, the viewer of the paintings is called to invite the saints into their own “communities” as intercessors. Phoebe is believed to have brought the epistle of Paul to the Romans, and thus she carries in her hand the epistle inscribed with ⲁϥϭⲣⲟ, Coptic for “victorious.” In the ancient Roman empire, administrative documents were sent around with the imperial seal to enforce edicts, often a reflection of the authority of those who decreed the letter. The Coptic inscription thus refers to Christ as the authority with which Paul the apostle sends his epistles with.

Christ and the daughter of Jairus

MARK 5:21–43 | MATTHEW 9:18–26 | LUKE 8:40–56

and Christ in Bethany

JOHN 12:1-8

In the inner space, Lazarus and Talitha are juxtaposed against each other. While Jairus intercedes for the healing of his daughter, Mary and Martha intercede for the healing of their brother. Christ delays in his arrival to both characters and, in His delay, manifests His glory in raising both from the dead. It is in both of these scenes that the family intercedes for the resurrection of their counterparts.

Although there were initial considerations to portray the raising of Lazarus, the scene of the three in their household corresponds more appropriately to the familial theme. Lazarus sits at the feet of Christ attentively, while “Martha served,” and “Mary took a pound of very costly oil of spikenard, anointed the feet of Jesus, and wiped His feet with her hair.” The humility of Mary is emphasised by the dark brown she has cloaked herself in. Although there seems to be a lack of consensus, various opinions link the narrative in John 12 to that in Mark 14 and Matthew 26. Elements of the other narratives were implied in the formation of this image, although it is primarily reflective of John 12.

christ as the good samaritan

LUKE 10:25-37

The scenes in the chapel conveyed various familial relationships- brother/sister, parent/child, and husband/wife - however, none related the perspective of those in isolation- those who are uninvolved in ascetical practices and also are not married or living with family. Christ as the Good Samaritan is thus presented as the fulfillment of that void, encompassing the duality of interpretation of the parable both literally and allegorically. The Church (the inn) is also a component in the familial relationship between Christ and the isolated and lonely. Sts Irenaeus, Clement, Origen, Gregory (the wonder-worker), Ambrose, Augustine and Ephrem the Syrian all concur that the Good Samaritan is Christ, an agreement that influenced the explicit representation of Christ as the Good Samaritan himself. Origen quotes a priest in a homily and describes the allegory of the Good Samaritan as a subscription to the following interpretation:

“The man who was going down is Adam, Jerusalem is paradise, Jericho the world, the robbers are the hostile powers, the priest is the law, the Levite represents the prophets, the Samaritan is Christ, the wounds represent dis- obedience, the beast the Lord's body, the inn should be interpreted as the church, since it accepts all that wish to come in. Furthermore, the two denarii are to be understood as the Father and the Son, the innkeeper as the chair- man of the church, who is in charge of its supervision. The Samaritan's promise to return points to the second coming of the Saviour.”

the baptism of cornelius

ACTS 10

The Baptism of Cornelius occupies a significant and central arrangement within the side room of the chapel, and is divided into two scenes. The bottom one depicts the vision of Cornelius (v.3-8). The upper scene depicts the Baptism of Cornelius and his household, with his “devout soldier” and family on the left, and Peter the Apostle on the right. Peter presents Cornelius to us, whose arrangement parallels that of Christ in the Theophany. The devout soldier, although not a member of Cornelius’ family, functions as the intercessor before Peter (with the two servants) for the household of Cornelius. It is through that intercessory role that Cornelius gains accession to the Church- bringing a duality of familial implication through this imagery. The first is the literal role of the soldier-intercessor in the baptism of a household (which mirrors the two other households within the same space), and the second is the unison of both Jews and Gentiles that occurs, a formation of a single body in the early Church, in which God “shows no partiality” (v. 34). Thus a culmination of the themes of family, intercession, the Church, resurrection and rebirth all manifest themselves vividly in the narrative of Cornelius. The family members on the left were painted in imitation of the Fayum mummy portraits that emerged from the period, dressed in a purple of regality which Cornelius has laid aside in a “self-emptying” rebirth (once again a kenotic behaviour that imitates the role of Christ in the Theophany).

text

Various texts have been inscribed on the undersides of the triangular trusses and entryways of the room, and they were chosen in collaboration with the owners of the room to emphasize the broader theme of family; they have been reproduced below.

“For where two or three are gathered together in My name, I am there in the midst of them.” Matthew 18:20

“Who is My mother and who are My brothers?” … “Here are My mother and My brothers! For whoever does the will of My Father in heaven is My brother and sister and mother.” Matthew 12:48-50

“If anyone hears My voice and opens the door, I will come in to him and dine with him, and he with Me.” Revelation 3:20

“For this reason I bow my knees to the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, from whom the whole family in heaven and earth is named.” Ephesians 3:14-19