glossary

Below are terms that may come up frequently when exploring the subject of iconography. The majority of these terms have been defined within a Coptic context.

icon

The word “icon” from the Greek “εἰκών” simply means image. Generally the word icon is used to describe a religious image of Christ and the saints or a Biblical or hagiographical narrative, in a variety of mediums.

Biblically, the term “icon” is used as early as the first chapter of Genesis:

“So God created mankind in His own icon, in the icon of God He created them; male and female He created them.” (Genesis 1:27)

“God made man in His icon, for in the icon of God has God made mankind” (Genesis 9:6).

In Genesis, the context is the creation of humanity as the icon of God. John of Damascus says, “the whole earth is a living icon of the face of God.” Humanity is described as vainly attempting to create “images” of worship thereon-after (twelve occurrences of צֶ֫לֶם in the Old Testament beyond Genesis), however in the New Testament the image (icon) of God is restored in humanity through the incarnation of Christ, the perfect icon of God.

The word icon first appears in the New Testament in the gospels (Mt 22:20, Mk 12:16, and Lk 20:24). After these occurrences icon appears yet again in the Pauline epistles,

“For those God foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the icon of his Son, that he might be the firstborn among many brothers and sisters.” (Romans 8:29)

“A man ought not to cover his head, since he is the icon and glory of God” (1 Corinthians 11:7)

“And we all, who with unveiled faces contemplate the Lord’s glory, are being transformed into his icon with ever-increasing glory, which comes from the Lord, who is the Spirit.” (2 Corinthians 3:18)

“The god of this age has blinded the minds of unbelievers, so that they cannot see the light of the gospel that displays the glory of Christ, who is the icon of God.” (2 Corinthians 4:4) This verse is of particular importance in expounding on the importance of the icon (and its role as a Light-bearer) in the contemporary world.

“The Son is the icon of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation.” (Colossians 1:15)

Thus the Church, both as a body and as a physical structure, are also seen as icons,

iconostasis

The iconostasis (Gk. ‘icon-stand, in referred to in Arabic as حجاب الهيكل [higab al-haykal, veil of the sanctuary] or حامل الايقونات [hamel al-ayquant, ‘bearer of the icons’]) stands at the boundary of the nave and the sanctuary, and thus functions as an entry point into the “holy of holies.” The iconostasis holds a complex position in both Coptic history and liturgy, and is often misrepresented as a “barrier.” It functions as a threshold of communion.¹ The iconostasis as it stands in most Coptic churches follows a structure developed in the 19th-20th century. Below is a diagram of the standard organization of icons on most Coptic iconostases today:

A: The Annunciation (royal doors)

B: Christ

C: John the Baptist/the Theophany

D: St Mark/local saint

E: The 12 Apostles

F: The Mystical Supper

G: Crucifix

H: John the Theologian

I: The Mother of God

J: The Mother of God and Christ

K: Local saint/the annunciation

L: Archangel Michael

(Diagram drawn by the author) The arrangement of the iconostasis is open to variation, however the central structure is loosely centred around the deisis: Christ flanked by John the Baptist and the Virgin Mary.

iconography

in general the term iconography is used to describe the system or language in which images and their elements communicate particular meanings associated with the group that has created or uses those images. In Christian art iconography refers to the general purview that involves the motifs used in Christian visual expression.

The suffix, “graphein” has caused some confusion in the usage of the words “iconography” and “iconographer.” In both Russian and Greek, the word graphos is used simultaneously to describe writing and painting (pisat in Russian). In contemporary usage the expression “writing icons” or “icons are written” derive from a mistranslation that has been given a spiritualization.²

iconographer

A compound of the Greek words eikon and -graphein, this term refers to an individual who creates icons. An iconographer may work individually, as part of a team, school, or workshop, and may specialize in panel or wall painting or also engage in other mediums such as mosaic or stained glass. Iconographers often undergo rigorous training, apprenticing under a “master iconographer” and immersing in the liturgical, theological, historical, and technical and artistic facets of iconography.

iconology

As opposed to iconography as the study of icons as a practice or discipline, iconology entails the study of icons as a field. Iconology aims to analyze the significance of iconographic subject matter within the parameters of the context, theological and cultural, that produced it.

iconoclasm, iconomachy

The term iconoclasm (Gk. icono- and clasm, lit. ‘destruction’) refers to the destruction or removal of icons and religious images, a controversy experienced in a variety of religions and time periods. The term iconomachy (Gk. icono- and machy, lit. ‘struggle’ from machein) refers to the broader process of resolution in understanding how and if images should be used in the Church.³

The use of images in the Church has always experienced a variety of attitudes, but the first “justifications” for the use of icons appear in the second half of the fourth century. These were characterized by an emphasis on the didactic, hagiographical, and narrational qualities of icons as installations that proposed imitation. Images were upheld as educational aids, particularly targeted towards the illiterate. The iconoclast controversy arose from a variety of opinions during the seventh-eighth century that regarded the icon as “idolatrous” as per Mosaic Law. The practice of proskynesis also fueled widespread concern. The Quintisext council introduced preliminary guidelines for a structural approach to iconography, with canons defining “appropriateness” for icons (see: theopropria). The council was emphatic on the importance of historicity over symbolism for the icon, as well as the importance of emphasizing truth over corruption. By the end of the seventh century and beginning of the eighth century, the societal, apocalyptic frenzy that contextualized these rising discourses also prompted a “purge” from the faithful of anything that may be profaning the faith- from icons, to relics, or veneration of the saints themselves. The desire for an “internal purity” to counter what seemed to be the repercussion of a “spiritual crisis” heightened the intense avoidance of anything that may be considered “pagan” or “intrusive.”

The 720s marks the beginning of the “image debate.” Various correspondences reveal scattered anxieties regarding the use of icons, however this does not acquire widespread concern until the 730s, and imperial involvement in the iconographic controversy begins in the 750s. In either 726 or 730 the public mosaic of Christ on the imperial gate was removed. In 754 a synod was held regarding the controversy. The synod declared that the representation of Christ in art negated His divinity. The iconoclasts claimed that the eucharist was the true icon of Christ, and that images of the saints compromised their agency. These were all later condemned as heretical, as to declare that the eucharist was an “icon” of Christ implied that it was not in fact Christ Himself. In 787 the second council of Nicea was held, and icons were restored in what is now celebrated as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy.” The primary defense was that God made Himself visible to humanity by becoming man, and to prohibit the depiction of God incarnate would be to deny the incarnation itself, an even graver heresy. St John of Damascus was an iconophilic writer from outside Byzantine who championed these ideas and heavily influenced the restoration of icons in Orthodoxy, declaring, “Therefore I boldly draw an image of the invisible God, not as invisible, but as having become visible for our sakes by partaking of flesh and blood.”

ecclesiology

Ecclesiology refers to the applied theology, theory, or practice that is concerned with the Church as an entity. When icons are defined as being “ecclesiological” it identifies their role as being ultimately concerned with the Church, as a body, and how it uses iconography.

proskynesis, aspasmos, and theopropria

The concept of veneration is central to how Christians engage with icons, and is expressed in a variety of ways.

Proskynesis (Gk. pros- [towards] and κυνέω, kyneo [kiss]) refers to the gesture of prostration or reverence before an icon, these gestures are expressions of supplication and admiration, and are not directed to the icons themselves, but their prototypes. Worship is solely directed to God.

Aspasmos (Gk. ‘greeting’ or ‘salutation’) refers to the practice of kissing icons as a form of greeting them, the practice was sanctioned during the second council of Nicaea (787 C.E.). The clergy and the faithful routinely greet Christ and the saints through icons during processions and reflects the Church’s belief that both the depicted and those who greet them comprise a single Body. Aspasmos is also a term that is designated to the hymns sung when the congregants greet each other in liturgy.

Theopropria (Gk. theo- ‘God’ and -propria ‘appropriate’ refers to that which is appropriate to offer to God, and extends into how icons can be regulated as gifts that are practical or useful in liturgy. The concept is closely tied the the first New Testament usage of the word “icon”

“Bring Me a denarius that I may see it.” So they brought it. And He said to them, “Whose icon and inscription is this?” They said to Him, “Caesar’s.” And Jesus answered and said to them, “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” And they marveled at Him.” (Mk12:13-17)

Christ uses this to command, “render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s, and to God the things which are God’s. Thus the image becomes the point of reference for the believer in discerning what ought to be given. The viewer stands before the icon and, regardless of the saint or Biblical narrative presented, are ultimately called to see the image of Christ. They are then, by extension, called by the icon to give unto God what is his. This call from the icon is twofold, it demands from the iconographer to “offer unto God from what is His” but also for the viewer to give, offer, not to the icon in and of itself, but to the One after whom the image takes likeness.

mosaic

An image or pattern produced by tessellating small colored pieces of tesserae, made of glass or ceramic. Due to the resistant nature of the medium, it is often installed in areas with high exposure to the elements, such as the outdoor exteriors of churches or in baptisteries.

In Egypt, mosaics are attested to in the earliest Coptic churches, such as in the site of Abu Mina in Mariout. The practice was revived in the Contemporary Coptic School under the hands of Isaac Fanous, Galal Ramzy, and their students.⁴

Images: Dr Galal Ramzy and Seham Guirguis create a mosaic of Christ Pantocrator for the apse of a Cairene Coptic Church at the Higher institute of Coptic Studies in the late 1980s.

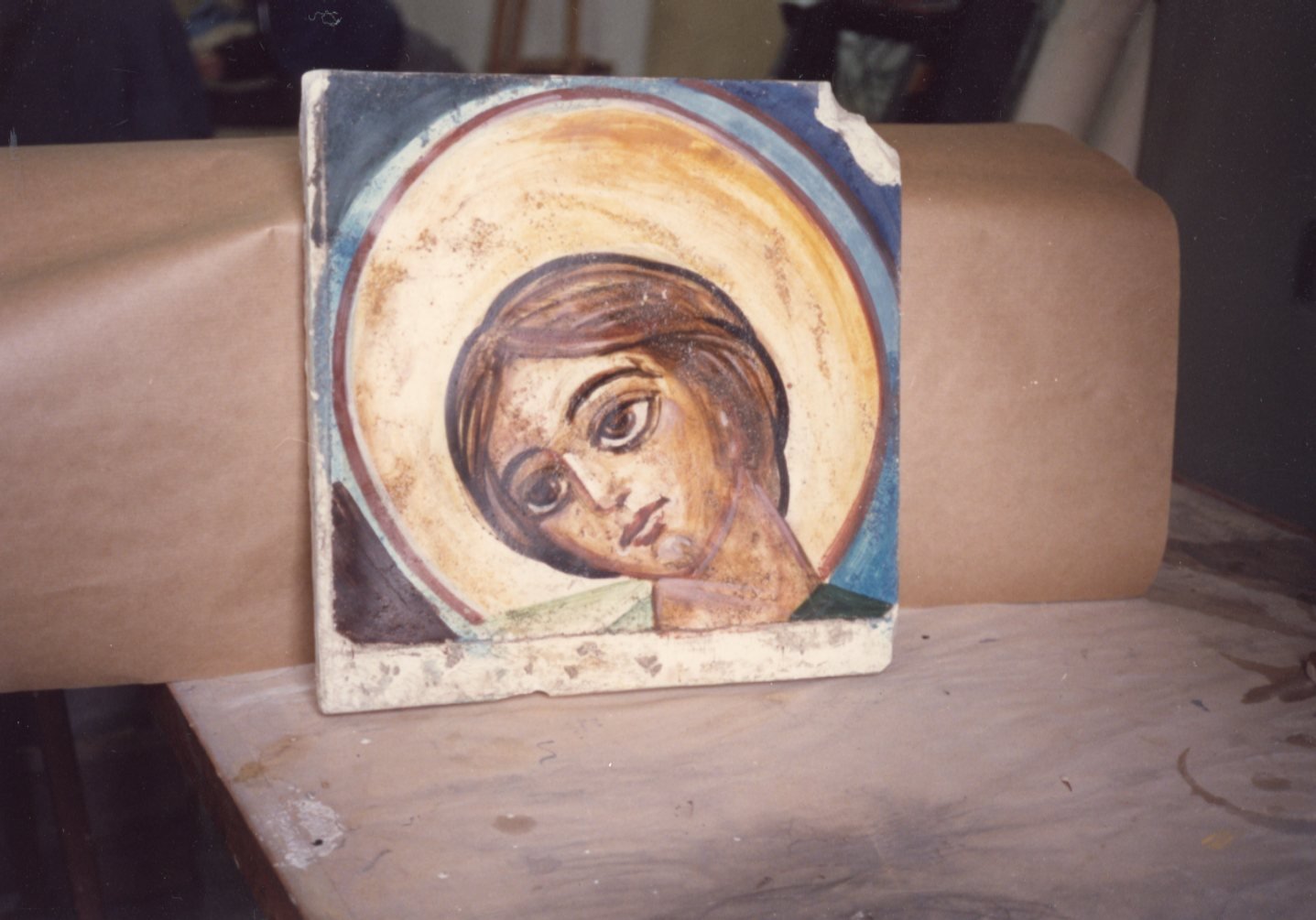

fresco

The word fresco, from the Germanic, fresca, refers to an ancient technique of mural painting that consists of applying paint directly on wet lime plaster. Due to the chemical composition of the plaster, a binder is not necessary and the pigment is instead mixed with water, producing a paint that sinks into the outer plaster, which itself becomes the medium or “binder” that holds the pigment. The pigment is absorbed by the wet plaster underneath and, after the plaster dries a few hours later, the chemical reaction produced fixes the pigment particles in the plaster. This enables the painting to have a very high tolerance and permanence, making it ideal for permanent installations and facilitating the preservation of many ancient works of art. This technique was also revived in the Contemporary Coptic school. ⁵

Images: Dr Isaac Fanous presents a technical demonstration in fresco painting at the Higher Institute of Coptic studies in the late 1980’s (photographs by Jaqueline Ascott) and details of Frescoes painted by Dr Isaac Fanous at the Monastery of St Pishoy in Wadi al Natrun, 1977 (photographs by Kirollos Kilada).

triptych

Triptychs are images constructed of three panels, often hinged together with two folding panels affixed to a central panel. The triptych which was largely popular in pre-Ottoman and Ottoman Egypt was also revived under Fanous and popularized by Bedour and Youssef. The triptych was an important form of media in the creation of private worship spaces, as the panel doors affixed to the central panel allow for a deliberate method of indicating active or inactive times for prayer. The construction of such “devices'' recalls the intimate architectural organization of niches in monastic cells.

Image: Contemporary triptych constructed and painted by Bedour Latif and Youssef Nassief, with Sts Antony (right panel) and Paul (left panel) and the Mother of God in the central panel.

apse

The apse is an architectural element located within the sanctuary, a large, often semicircular recess in a church, at the easternmost end and is behind the altar. As the worshippers face the east during the liturgy, the apse is often the focal point of the space, in addition to the altar and dome.

Most Coptic apsidal spaces include a set of steps affixed to them, identified in various manuscripts and liturgical manuals as the ⲥⲩⲛ ⲑⲣⲟⲛⲟⲥ (“Sein thronos” lit. “co-throne”).⁶ As early Coptic church architecture derived itself from that of the Roman basilica, the steps- once reserved for magistrates and authorities- shifted in the late antique Christian basilica to be used by the clergy and hierarchs overseeing the liturgical service. The clergy and hierarchs would sit on the ⲥⲩⲛ ⲑⲣⲟⲛⲟⲥ and preside over liturgical celebrations and deliver homilies from there in the early period.

In terms of Tradition, the consistent theme in the Coptic Church for the apsidal space is an eschatological ascension (or an abbreviated form or variation of it), with a bottom register that consisted of various combinations of the Virgin Mary, apostles, patriarchs, local monastic saints, prophets or angels. Thus the hierarch seated at these steps was declared, through this visual system, the successor of an apostolic liturgy, but more importantly, the believers would look towards a simultaneous image of the ascent and return of Christ; with both events believed to be oriented towards the east and with the Virgin enthroned functioning as an icon of the eucharist itself. In the late twentieth century this tradition was abandoned in favour of depictions of the events in Revelation.

Image: Design by the author of the traditional scheme for a Coptic apse- Christ ascends and returns from the east, the icon is also an image of the whole Church, the Eucharist, the resurrection, it is an embodiment of the entire liturgy.

proplasmos

Derived from the Greek, "proplasmos" (πρόπλασμος and “sankir” in Russian) means "formation" or "shaping." The word is derived from the verb "proplássō" (προπλάσσω), which means "to form" or "to shape." It is used to describe the darkest, initial layer of colour upon which light is modeled with successive layers of paint, bringing the icon “from dark to light” or “to life.” You can learn more about the process here.

abstraction

The removal of elements in the visual expression an object to create a 'simplified form’ or, as the Tate defines it, “produce something which ‘has no source at all in external reality.”⁷ Abstract forms or art, including icons, simplify the subject matter to its most basic and important features. The level of abstraction can vary, and the artist (or iconographer) can be very decisive and intentional on what is communicated to be "important" or not. Abstraction enables the artist's freedom to create an image that is beyond the containment of time and space, emphasizing the internal reality of what is depicted, but still present in physical reality.

taboric light

“Taboric” relates to the Transfiguration of Christ, situated on Mount Tabor, as described in the gospel accounts. Sometimes icons are described as being Taboric; The experience of the transfiguration expresses the declaration of God in announcing, “this is My beloved Son.” The second Person of the Trinity reveals Himself to the viewer in the icon, a divine paradox. The icon acknowledges the insufficiency of the human visual language to contain God, and thus extends beyond itself- in abstraction, the use of visual principles are manipulated to emphasize the importance of light as the vehicle for sight and vision, and thus an icon, or an image that is “taboric” calls the viewer to climb mount Tabor and witness the light of God.

beauty

Across many discourses, various Greek words have been used in an attempt to describe the concept of beauty in iconography,

καλός (kalos) a polysemous word that translates synonymously into Beauty, Goodness, and Truth. These three characteristics form a type of “trinitarian” assemblage in how the icon functions as beautiful- the icon is truthful, thus making it good, and revealing a true beauty, and vice-a-versa. Thus when an iconographer composes an icon, they are composing a type of philokalia, out of a love of kalos. Paul Evdokimov was a theologian who used the term kalon extensively to describe the icon:

“The Creator, like a divine poet, in bringing the world into being out of nothingness, composed His symphony in six days, the Hexameron. After each one of His creative acts, He “saw that it was beautiful.” The Greek text of the Biblical story uses the word kalon- beautiful, and not agathon- good; the Hebrew word carries both meanings at the same time.”⁸

Dr George Kordis, a prominent Greek iconographer, has also used other Greek words to describe the concept of beauty,

ωραίος (ouraios), beauty through the lens of time rather than aesthetic. An example that Dr Kordis gave was a fruit- once it has matured in due time, it is at its optimal state for consumption and thus has the most to offer to the consumer.

όμορφος (omorfos), well shaped, having form, existent, an antonym for formlessness, in which the “reality” of something’s beauty is expressed in its incarnate form

mimesis

Derived from the ancient Greek μιμεῖσθαι (mimeîsthai, “to imitate”), mimesis is the state of an icon in which it imitates reality, but in reverse also calls the viewer to participate in that same reality through imitation, or enactment.

liturgy, eucharist

Liturgy (Gk. Leitos- “public” and -ergos “working”, work of the laity, or work of the people) is believed, by the Church, to be the cosmic union of the heavenly and the earthly in the body of Christ in the people. This can be expressed through the worship of the Church, in music, art, architecture, poetry, and the Word of God, culminating in communion but extending into the world beyond the walls of the Church.

Eucharist (eukharistia “thanksgiving” from eu ‘well’ + kharizesthai ‘offer graciously’ [from kharis ‘grace’]) is believed to be the mystical kenosis (self-emptying) of God, who is offered on the altar during liturgy as the "Bread of Life” in which the faithful unite with God.

halo

The Greek origin of the word halo (also referred to as a nimbus), ἅλως, refers to a “threshold” and was used in one of two contexts, sometimes to refer to the ring of light surrounding the sun and moon, as well as the boundary of a threshing floor. Thus in an icon, the halo identifies the figure as the central threshold between heaven and earth, an embodiment of Christ that is expressed through a disc of light that emanates from the figure’s head. The halo is universal to most figural forms of religious art as a marker of sanctity and holiness. In Christian iconography, the halo of Christ is demarcated by a cruciform shape that surrounds His head. In ancient Egyptian art, the sun disc as an embodiment of light also appears behind the heads of the deified, and prefigures the use of a sun-disc as a halo.

mandorla, clipeus

A mandorla (Italian for almond), or a doxa (Gk. “glory”) can be circular, almond-shaped (vesica piscis- the shaped formed by the intersection of two circles) or oval. It functions as the iconographic expression of a moment of glory that transcends time and space. The centre of a mandorla is darkest, becoming lighter towards the outer ring, best described in the apophatic theology of luminous darkness expounded upon by the likes of Clement of Alexandria, Origen, the Cappadocian Fathers, Dionysios the Areopagite,⁹ and Maximus the Confessor. The “edges” of a mandorla may also appear in the top or corners of an icon, and the depicted gravitate towards these expressions of light, which may have a bust of Christ or the hand of God extending from it, blessing, crowning, or speaking.

The clipeus (or imagines clipeatae) is a circular shield, that usually bears a bust of Christ or image of a cross or a ☧ (chi-ro), and is usually seen in the hands of Archangel Michael. In antiquity, the clipeus was a shield either worn in battle or displayed publicly that sometimes bore the image of the emperor and thus, with military association, declared that the emperor was victorious. In the Christian appropriation, Michael, as head of the heavenly, declares Christ as victor.

Images: Left, a detail from the apsidal mosaic of the Transfiguration at the Monastery of St Catherine, Mt Sinai, Egypt (6th-7th century), with Christ depicted in a mandorla. Right: detail of a clipeus in the hand of archangel Michael depicting the risen Christ, icon by the author.

deisis

δέησις (deisis, Greek for “prayer” or “supplication”) is an iconographic composition that consists of Christ in the centre, flanked by the Mother of God and John the Baptist on either side of Him. The arrangement is, in some shape or form, central to virtually all iconostasis programs, as the iconostasis is the threshold between heaven and earth, as are the supplicants, or intercessors. Extensions to either side of the deisis through additional angels, evangelists, or apostles, form a “great deisis.”

Image: A deisis composition painted by the Ottoman iconographers Ibrahim the Scribe and Yuhanna the Armenian, in situ at the Church of St Barbara in Old Cairo.

maniple, maphorion

A maniple is a small linen cloth that the priest wraps over his arm or hands to either hold or wash the Eucharistic bread (in the catholic rite the priests face and hands). Variations of this cloth are identified as a “mappa” or “mappula” (Classical Latin for “table-napkin”), initially used an imperial context and later part of the liturgical one. A “palla” (like “mappula”) is a small cloth the deacon holds the chalice with.

Despite the variety in names, origins, or forms, a small, thin cloth in the hands of the Mother of God or clergy identifies that the figure in the icons is a “bearer” or “carrier” of the body of Christ. Angels and other figures may also be seen holding these cloths outwards, so as to say that they are “receptive” to receiving the body of Christ.

Images: Left, a maniple in the hand of a patriarch, right, a maniple in the hand of the Virgin Mary carrying Christ. Both wall paintings are from the Monastery of the Syrians in Wadi al Natrun, Egypt (8th-10th century). Photographs by the author.

-

J., Gerstel Sharon E. Thresholds of the Sacred: Architectural, Art Historical, Liturgical, and Theological Perspectives on Religious Screens, East and West. Dumbarton Oaks, 2007.

https://russianicons.wordpress.com/2011/08/31/is-an-icon-painted-or-written/

Brubaker, Leslie. “Icons and Iconomachy.” A Companion to Byzantium, 2010, pp. 323–337., https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444320015.ch25.

Ascott, Jacqueline Ann. “Towards Contemporary Coptic Art.” PhD: Art: Cairo, Higher Institute of Coptic Studies.

Ibid

Al-Maqari, Athanasius. “Lectures on the Liturgical Rites of the Coptic Orthodox Church.” Features of the Alexandrian Liturgical Rite. Los Angeles.

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/a/abstract-art#:~:text=(1910%E2%80%931)-,Tate,have%20been%20simplified%20or%20schematised.

Evdokimov, Paul. The Art of the Icon: A Theology of Beauty. Oakwood Publications, 2000.

https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/brilliant-darkness-on-st-dionysios-the-areopagites-blue-halo/#_edn3