the iconostasis

this project primarily entailed the creation of a series of icons for an iconostasis, and an exploration of how the icons of the iconostasis could corroborate and support each other, functioning as its own “program.” In this iconostasis, the congregation is greeted with messengers, who bring forward the good news of resurrection and victory of Christ.

The iconostasis stands at the boundary of the nave and the sanctuary, and thus functions as an entry point into the “holy of holies.” The iconostasis holds a complex and misunderstood role in both Coptic history and liturgy, and is often misrepresented as a “barrier.” It is in fact, a threshold of communion.

christ enthroned

Christ is dressed in a gold himation and a white tunic, and holds His right hand in blessing (His hand forms the letters I and C, and thus, like the clergy, He blesses us with His name) and in His left hand carries a gospel book. Traditionally He is dressed in red to symbolize both His salvific bloodshed and His humanity-however in this icon His humanity is fully announced in His incarnate form, and His sacrifice, in His hands and feet, making any additional symbolic reiteration redundant. The gospel book is in and of itself an icon of Christ, Christ being represented by the central cross and surrounded by four smaller crosses- the evangelists. Above and below this is inscribed, in Coptic, the first line from the gospel of St John- “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God…” The gospel cover is inspired by a variety of Coptic gospel cases produced between the fifth and sixteenth centuries, where the opening line of the gospel was often inscribed on the top and bottom borders of the gospel as an identifier. Christ is seated in a garden, clothed in glory, He is the new Adam.

Coptic wall painting of Christ Pantocrator flanked by two angels, from the Monastery of St. Jeremiah in Saqqara, 6th–8th century AD (now in the Coptic Museum, Cairo; photograph by Carole Raddato) and an accompanying sketch

Cover for the Gospel of St John, from the Church of St Mercurius in Old Cairo, 13th-14th century.

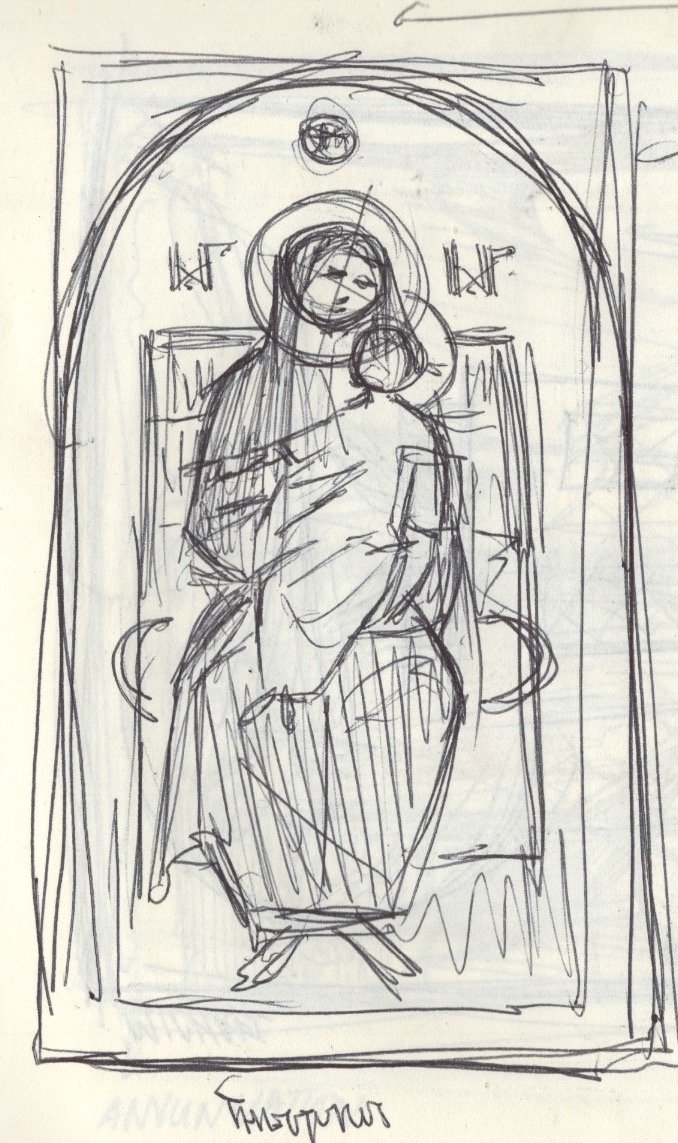

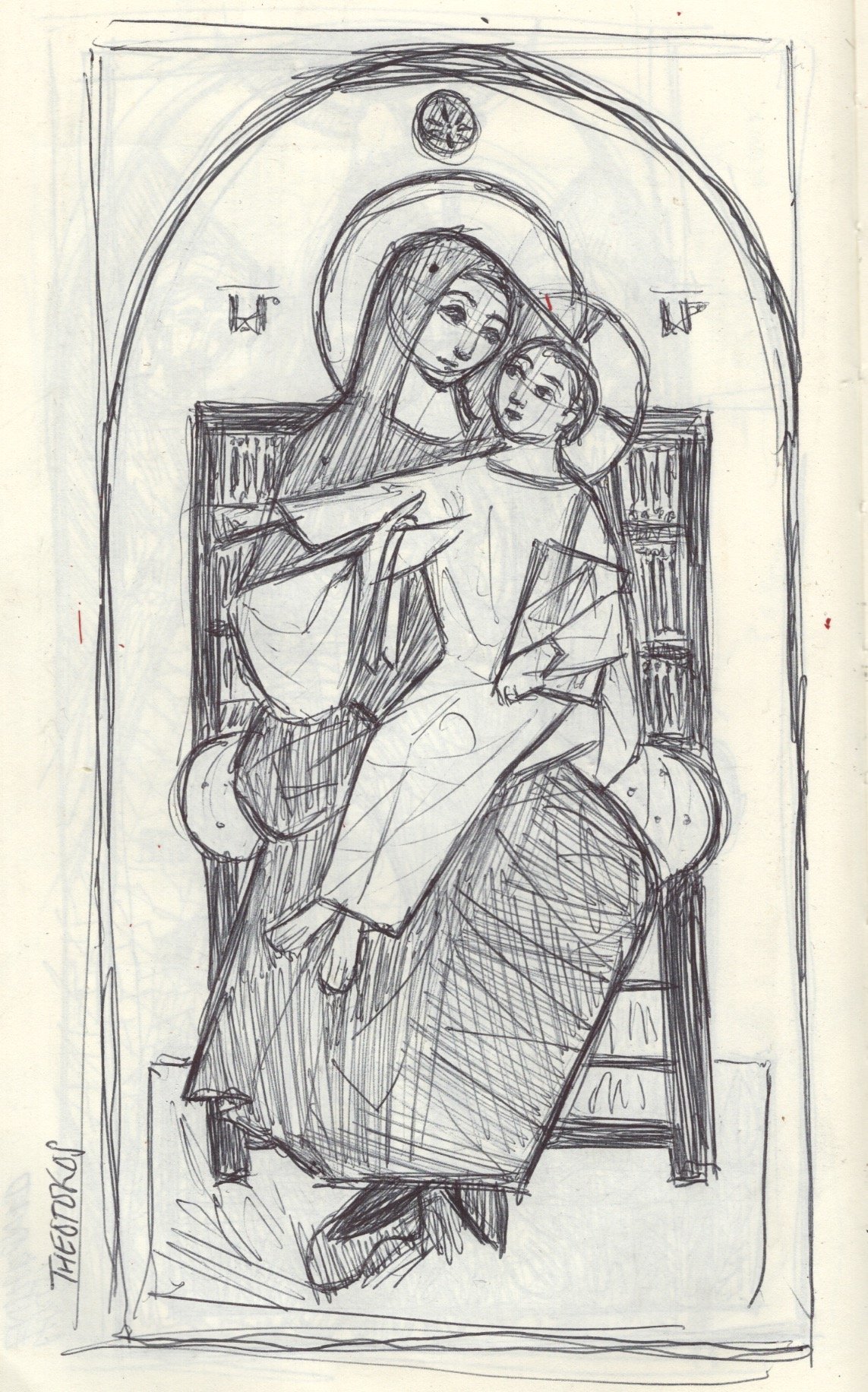

the mother of god enthroned

The icon of the Mother of God is one of the most important icons, and one can read it as an “icon of everything”: incarnation, love, humility, sacrifice, entombment, birth and rebirth, creation, intercession, the Church. All these themes also appear on the other icons of the iconostasis, and culminate in this one. As St John of Damascus proclaims, "the only name of the Theotokos is the Mother of God; this name contains the entire mystery of the economy of salvation.” As the Divine Child sits enthroned on His mother’s lap, one cannot help but wonder how the infinite Mystery reveals Himself as a simple child: playful, pure, loving, beautiful. Veiled in His mother’s brown veil, we see in it the earth that veils His body within the tomb, and rising upright from her lap He declares His victorious resurrection. With one hand He clasps onto the nourishing Word, with several wheat stalks that allude to Him as the Word, the Bread of Life. Inscribed onto the scroll is ⲡⲭ︦ⲥ︦ ⲁϥϭⲣⲟ, “Christ is victor,” and with His other hand He blesses the viewer. He stares into the eyes of His mother while declaring the victorious love that His sacrifice will soon define. While Mary is the second Eve, she is also the earth, all of humanity, garbed in her brown veil, formed from dirt, earth, from which the new Adam is born. At her feet is a red glow, a fiery emanation between the leaves of the garden she sits in- and this alludes to her typology as the burning bush. Her hand raised presents Him to us, offers Him to us, in a work of the people-a work of humanity-a true liturgy of love. “In the Virgin, all of humanity gives birth to God… in her, all have said, “yes, Lord come!” (Evdokimov). The icon is the ultimate image of communion between the human and the Divine. With her hand she also intercedes, she who is gazed upon by the Sun in this very moment directs her gaze at you, mother to all, hope to all, ladder to the One, her presence rings as a melody of victory, as “God has become man that man might become god” (St Athanasius, read more here). In her other hand is a small white cloth, (can be described by a variety of terms: maniple, mappa, mappula, palla) used by the clergy to wrap the Eucharist in. Here, at the door of the sanctuary, Mary mirrors the priest in that she, too, holds in her hands the Bread of Life.

the annunciation

The icon of the Annunciation, traditionally, belongs on the royal gate to the sanctuary. In this icon, Gabriel steps forward towards Mary and announces both to her and the viewer, “Hail to you, full of Grace, the Lord is with You.” Emmanuel, God with us, is on the altar, and with this icon on the iconostasis,

“For the offering of bread and wine to pass into the sanctuary during the Liturgy, and for the Body and Blood of Christ to come out from the altar to the congregation, [the gifts must pass through the iconostasis]. This reinforces the fact that the synergy of God and mankind is required not just for the historic Incarnation but for every person's union with God through Holy Communion. Both God's initiative and the Virgin Mary's 'Amen' were prerequisites for the Incarnation, and therefore also for each Christian's participation in the Body and Blood of Christ. For the Eucharist to be possible the Word had to become flesh; the Liturgy is predicated by the Annunciation.” (Aidan Hart, Festal icons)

The central point of the central axes in the composition is the angel’s hand, who gestures (with ancient oratorical gesturing) with his thumb touching his ring finger the commencement of an important announcement, the proposed union between God and man. The hand conveys a question, proposition to both the viewer and Mary- and in her we say, “yes Lord, come!” Gabriel carries in his hand a messenger’s staff and an olive branch. An olive branch also appears in the mouth of the dove at the Virgin’s feet, and alludes to her Matins doxology- the pure turtle dove that declares the reconciliation between God and man to Noah, now declares to us this reconciliation in the annunciation- “For that dove has declared unto us the peace of God toward mankind.” Mary here also stands in a garden, one out of which, as described in the Vespers doxology, she is called out of by Solomon. Raising one hand in obedience to the Divine Will, in her other hand she holds a spindle wrapped in crimson thread. This derives from the apocryphal tradition that during the annunciation, Mary was spinning the scarlet thread for the temple curtain. She is overshadowed by a domed building, which is the Church, she is the Church, containing the Body of Christ, and as st Gregory of Narek exclaims, “If one were to write that the Theotokos is the icon of the Church, one would not be unjustified.” The inscription of the icon reads ⲡⲓⲉⲩⲁⲅⲅⲉⲗⲓⲥⲙⲟⲥ.

Pictured is a compositional breakdown for the icon of the annunciation: the icon is divided in two halves, the left bearing the heavenly realm (and its delegation) and the right bearing the earthly one (its receiver). The hand (icon of the good news) is central, and the heavenly realm sweeps in and enters into the earthly one.

saint mark

The icon of St Mark consists of him dressed in a pallium, as a cleric, carrying a gospel book and standing on the Alexandrian shore. The apostle stands, announcing the good news to the viewer, and from his feet sprouts a paradisiacal garden- he irrigates the soil of Egyptian land with the life-giving Word. Like the gospel in the icon of Christ, this gospel book is inscribed with the first line of the gospel of Mark, “The beginning of the good news about Jesus the Messiah, the Son of God…” Good news, in Greek, is εὐαγγελίου, the same word inscribed on the icon of the annunciation- Mark, like Gabriel, announces the good news, and one can notice the scene of the annunciation painted onto the hem of his garment on the two yellow appendages. Here the role of angel and evangelist are related- both are messengers. The second verse of Mark’s gospel describes John the Baptist as a messenger, and thus, accompanying Christ and Mary are four messengers: Michael, Gabriel, John the Baptist, and Mark. All four bring forward the good news to the people, as do the deacons who read the readings. All the martyrs on the iconostasis are cloaked in red, they are witnesses (martyria) to the Logos. The gospel cover is inspired both by Coptic gospel covers and funerary stela from the late antique period. On it is an ankh, the ancient Egyptian icon of life, holds a laurel wreath, and in its head is the cross. The inclusion of the ankh corroborates the evangelist’s message that the good news has arrived, and the laurel wreath, the symbol of victory, indicates that this message of victory is that of the resurrection. Two birds flank the ankh, which is crowned with the cross, the completion, fullness, and perfection of the life of the Egyptians. The ankh, once a Pagan symbol, now becomes, to Egypt’s first Christians, the signal of the victory of Christ. At his feet is Anianos, the patriarchal successor of St Mark, and he, too, carries the good news and is dressed for the work of and for the people. One of Mark’s sandals is ripped- Anianos, his cobbler, becomes the successive leader. The lighthouse of Alexandria is depicted capped with a cross, as the Church of Alexandria becomes the house of light for the country. St Mark is always depicted with a lion- an element of the tetramorph, he is associated with the lion largely for two reasons: the first being a parallel between the voice crying in the wilderness (Mark 1:3) and the roar of a lion, and the second being a tale related by Severus Ibn Al-Muqaffa,

"Once a lion and lioness appeared to John Mark and his father Arostalis while they were traveling in Jordan. The father was very scared and begged his son to escape, while he awaited his fate. John Mark assured his father that Jesus Christ would save them and began to pray. The two beasts fell dead and as a result of this miracle, the father believed in Christ."

Pictured: A panel portrait and wall painting (Bawit) of St Mark the evangelist at the BNF, dating to the sixth century and among the earliest available images of the apostle in the Coptic repertoire. Depicted in a pallium as a bishop he carries the gospel book and, in the case of the Bawit fresco, is accompanied by a personification of the Church. On the right is an egg-tempera study based on the two available portraits.

Also pictured is a detail of a Coptic textile from the Cleveland Museum of art, dating to the sixth century and depicting a crux ansata, an iconographic motif of the resurrection that existed in manuscripts, textiles, wall paintings, stela, and other media and inspired the gospel cover design.

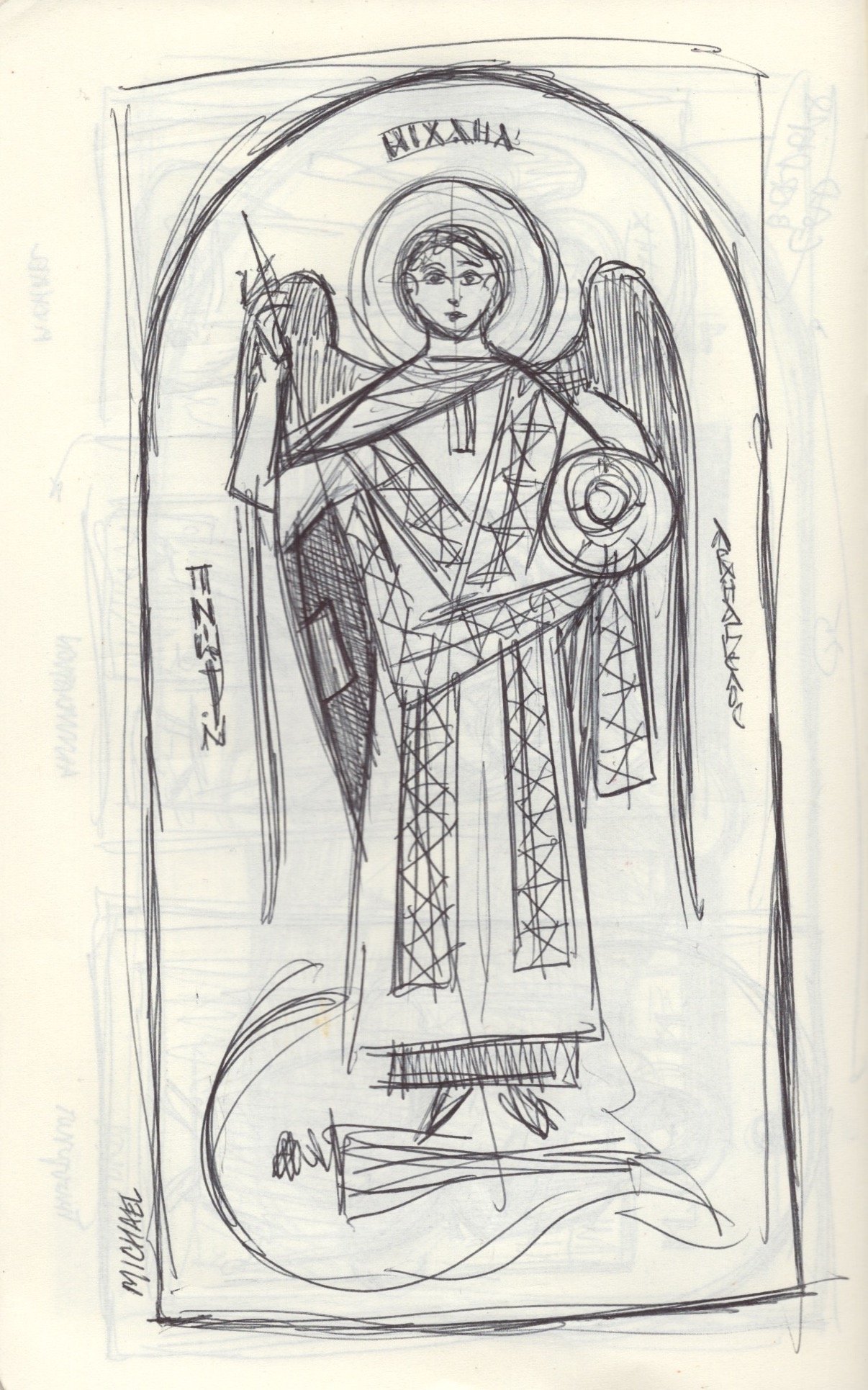

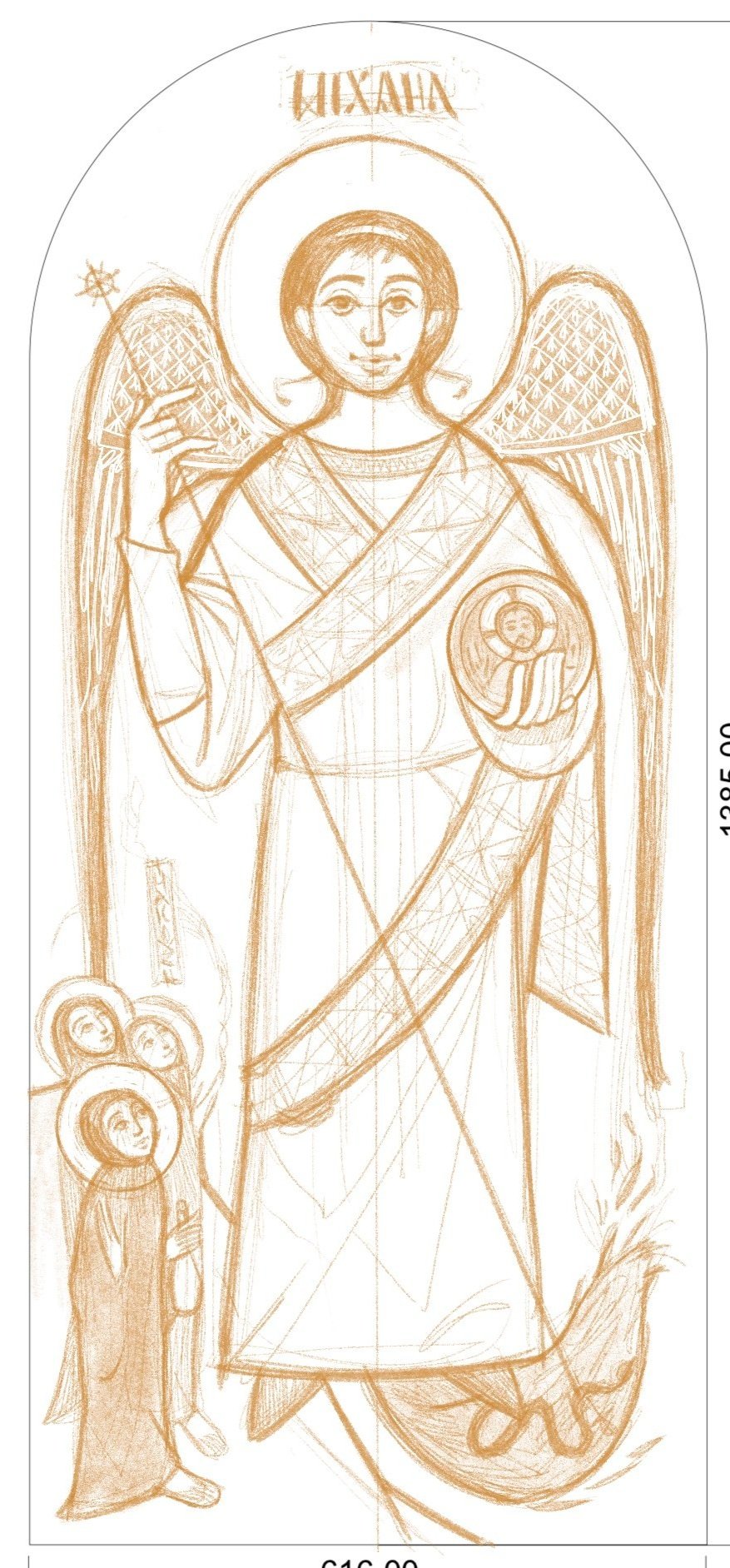

archangel michael

The icon of archangel Michael depicts Michael standing victoriously, spearing Satan, and carrying a clipeus in his hand depicting the risen Lord, who shows His hands to the viewer. Three women stand at his feet- they are the myrrhbearers. Michael in this icon tramples Satan, but also announces the victory of the resurrection, first to the women at the tomb, then to the viewer. He, whose name in and of itself is a question (מִיכָאֵל, who is like God?”) asks, “Why do you seek the Living among the dead?” (Luke 24:6). The clipeus (or imagines clipeatae) is a circular shield, that sometimes also bears and image of a cross or a ☧ (chi-ro). In antiquity, the clipeus was a shield either worn in battle or displayed publicly that sometimes bore the image of the emperor and thus, with military association, declared that the emperor was victorious. With its re-appropriation in Christian imagery, Michael, the head of the heavenly legion, declares the victory of Christ over death at the door of the tomb. This then connects all the icons as containing the delivery of the message of salvation, the good news, from the sanctuary to the people. The deacons also deliver this message, from the same location, and thus both Michael and the deacon are dressed in the same manner.

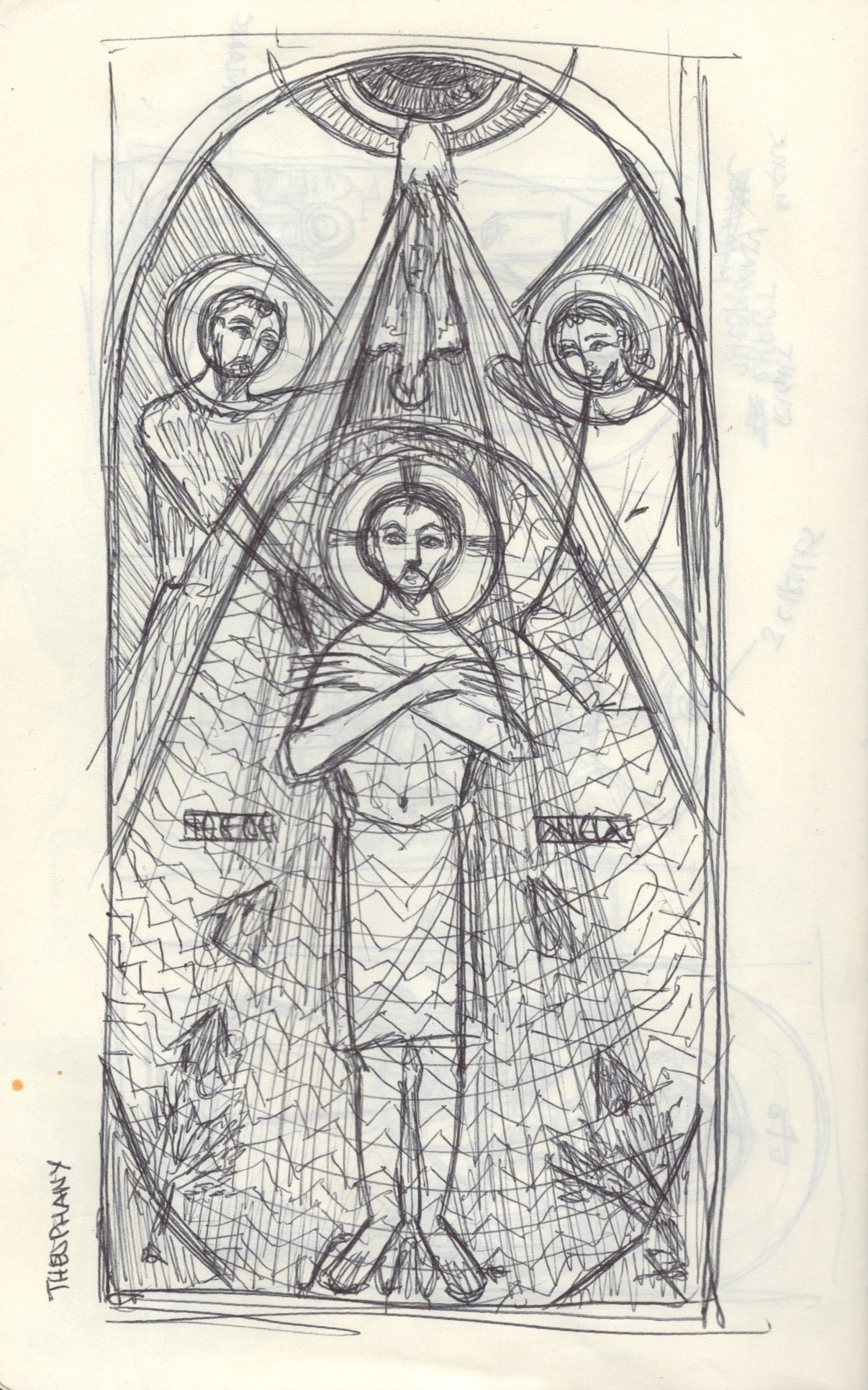

the theophany

The icon of the Theophany consists of Christ, flanked by two angels and John who baptizes Him. Christ is contained within a “coffin” of water, with his arms folded over his chest as one Who is buried, and the waves form a shroud over His body, and the icon of His baptism also becomes one of His burial. In this icon the Trinity is also present, and the Theophany (θεοφάνεια, literally, manifestation of God, phaínein meaning to “bring light”) thus is also an icon of the Trinity. Emerging from heaven, at the top, is a hand that holds two fingers forward- the oratorical gesture that identifies a speaker. This hand thus is not the physical hand of God the Father (the Father is never depicted incarnate), but rather an icon of the action of speech, and an icon that identifies Who the speaker is. The hand functions in this way like a “stop” sign, for instance, and has been used as a visual device from the inception of Christian art. The Trinity is signified by a single, vertical axis that connects across the centre of the icon and stretches from heaven and into the depth of the earth. Heaven and earth are also juxtaposed horizontally, with the angel as the heavenly messenger and John the Baptist as the earthly one. These two axes form a cross, and through the cross Christ descends into the earth and raises us up with Him, first in the prefigurement of baptism and then in this resurrection.

The compositional formation of John and the angel is inspired by ancient Egyptian scenes of the purification of Pharaoh who, in ancient Egyptian theology, was believed to be reborn ceremonially, daily, through water. The composition also mirrors that of the descent into Hades and the three holy youth, all themes that are both liturgically and iconographically tied together through the resurrection- in icons, this is done through composition (as shown below). In the water are four fish, symbolic of the four gospels. The angel at the bottom holds a cloth over his hands to “receive” the body of Christ and, like the maniple in the icon of Mary, the pallium around St Mark’s neck, and the cloths on the table in the icon of the Eucharist, it is adorned with small crosses that indicate that it is a liturgical object, and that the event at hand is mirroring liturgy. The tree bearing good fruit stands tall at the feet of John the Baptist, alluding to his homily in Matthew 3:10, and, spared from “death” (fire) participates with the rest of creation in the joy of Life.

Pictured: the “resurrection” composition, in which descent also implies ascent, the axes for a cross, (second image), and the central figure (Christ) brings humanity with him (surrounding figures).

Also pictured is a twelfth-century (1178-1180 C.E.) detail from the Tetrevangelion, now in the Bibliotheque-Nationale de France. It is one of many examples in which a hand is used to indicate the blessing or speech of God the Father.

the mystical supper

The icon of the Mystical supper centres on Christ breaking bread. He rests with His apostles in a vineyard, He is the true Vine, and in a wheat field, He is the bread of Life. The table is furnished as an altar, He is the High Priest. Christ and the apostles are all dressed in white, they all participate in the heavenly liturgy. Judas, who leaves the scene, is neither animated by light or form, but rather becomes a shadow of darkness that voids itself from Christ’s life-giving light. Ultimately, the icon is of Christ breaking Himself for the viewer. The viewer stands opposite of Christ, It is at this table that the viewer, the participant is called to offer their love to Love Himself, declaring, “Let us get up early to the vineyards; Let us see if the vine has budded, Whether the grape blossoms are open, And the pomegranates are in bloom. There I will give you my love” (Song of Songs 7:12).